More than $4 million in funding from the governor’s office will breathe life into plans created by UGA’s Institute of Government—giving one Gainesville neighborhood a pathway to a brighter future and stronger community.

The grants, part of an overall package of more than $225 million for 142 projects across the state, are meant to improve neighborhood assets like parks, recreation facilities and sidewalks in communities disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The city of Gainesville and Hall County will receive $2.2 million each to support projects in “A Vision for the Athens Street and 129 South Corridors,” a community-driven plan focused on increasing greenspace and connectivity released last year by the University of Georgia Institute of Government.

Leigh Elkins, UGA faculty and project lead, said the funding is a welcome boost to an area in need.

“These projects have the potential to transform a neighborhood by giving people central places to gather for generations to come,” she said.

Barbara Brooks, a retired social worker and Gainesville Ward 3 councilwoman, was a driving force in the development of the plan.

A Jackson County native, she remembers traveling to Athens Street as a young woman in the mid-1960s, when the area was the centerpiece of Black culture, including the homeplace of education pioneer Beulah Rucker Oliver and the iconic E.E. Butler High School.

“Out in the county, there were no places for people of color to go. Gainesville was attractive because on Athens Street there was a movie theater, drug store, record shop, and many other businesses owned by Black people—it was a thriving little community,” she said.

Over the years, the area became fractured due to the widening of U.S. 129, which displaced businesses as well as families. Within decades, what was once an inviting gateway to Gainesville had become unattractive, unwelcoming and disconnected from the rest of the city.

To address such issues, UGA Institute of Government faculty and staff worked with citizens, city planners and elected officials to create a vision and implementation plan for the area. The full-color, 100-page plan includes recommendations such as building a network of sidewalks and crosswalks to improve pedestrian safety and installing streetscaping and art to visually and physically connect the area to the rest of Gainesville.

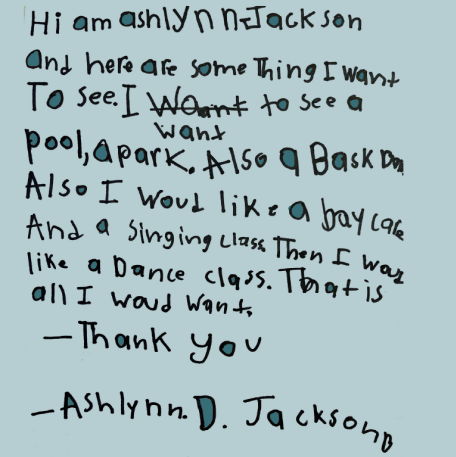

Community input is important to vision and strategic planning. For Athens Street, the process included asking for input from school-age children like Ashlynn D. Jackson, who wrote a letter of things she’d like to see in her community, including a pool, park and daycare. Her charming appeal struck a chord, according to Gainesville City Council member Barbara Brooks. “I think it touched the heart of everybody on that steering committee. If little kids know something is missing from their community, what are we waiting for?” she said.

The plan is the latest offshoot of a decade-long partnership with UGA that started with the city investing in the Renaissance Strategic Vision and Plan (RSVP) process. The three-step method gives communities a road map for economic development and has proven successful for Gainesville—city officials report $318 million in private investment in downtown and the Midland area in just the last five years.

Elkins said tapping into the community and teasing out residents’ ideas and insights is a critical part of the UGA process.

“Everything that’s in these plans is what they’ve told us they want. The people who live in a place are the experts on that place, and they know what’s best,” she said. “It’s our job to help figure out how to envision that.”

One challenge to the Athens Street corridor is convoluted zoning between the city and county. Elkins describes pockets where properties next door to each other are under different sets of code, presenting problems for residents and developers alike.

UGA recommended the city and county agree to shared enforcement codes through a memorandum of understanding (MOU).

“We wanted to create a level playing field and eliminate confusion within the neighborhood,” Elkins said.

Equally important for development is fostering community buy-in.

Jessica Tullar, housing and special projects manager in Gainesville’s Community Development Department, says thoughtful public engagement helped energize the people and businesses around Athens Street.

“We tried hard to involve people who perhaps aren’t thought of as a squeaky wheel but who are insightful and engaged,” she said of the RSVP process. “We listened to business and property owners, nonprofits and activist groups, and city officials.”

If recent funding is any indicator, the formula for Gainesville seems to be working. Brooks said it also shows the commitment local and state governments have to implementing plans to revive communities.

“The city’s ability to move forward on projects that promise such a positive impact on the neighborhood by enhancing walkability brings us closer to restoring Athens Street to the vibrant and thriving corridor it once was,” she said.

Homegrown Talent: Gainesville native Leigh Elkins plays an active role in city’s renaissance

Watching her hometown progress and plan for the future is exciting for Leigh Elkins, faculty in the UGA Institute of Government’s Planning and Environmental Services unit. “Both professionally and personally, it’s been fun to see how the community has grown, how much more it offers, and that I’ve had some role in the process,” she said. The city’s activated downtown space continues to radiate outward, connecting new neighborhoods via trails and a greenway, serving as a model for 21st century economic and community development. “Gainesville has seen tremendous growth over the past 30 or 40 years, and they haven’t been afraid of it. They’ve recognized that to be ready for growth you have to have a plan so you can shape it into what’s most appropriate for your community,” she said. Elkins credits her parents—now retired but still active volunteers—with inspiring her work. “Both of my parents truly modeled what it was like to serve others—and I think that’s probably why I ended up in public service,” she said. A commitment to people and places like Gainesville continues to motivate her. “We kind of owe it to Georgia,” she said of UGA’s land-grant status. “It also takes everything that happens at the university out into the state in an approachable and meaningful way. We should be figuring out solutions for our communities to help them thrive.”